But only in Hobart, when we landed at the airport on Sunday 13 May.

But only in Hobart, when we landed at the airport on Sunday 13 May.

The true Tasmanian devil is a rare marsupial that lives only on the Australian island state of Tasmania. But the spunky doglike animal is rapidly disappearing. It has been declared an endangered species, being wiped out by a rare cancer called Devil Facial Tumour Disease (DFTD).

Tasmanian devils play an important role in keeping the state's ecosystem in balance. They keep the population of other predators, such as foxes and feral (wild) cats, in check. Ray Nias, head of World Wildlife Federation-Australia's conservation program, says all Tasmanian wildlife will suffer if the devil becomes extinct. ‘If the devils go and the foxes and cats increase, it would be all over for a good dozen or more species of mammals—many of which are unique to Tasmania.’ Tasmania's Primary Industries Minister, David Llewellyn, said, ‘The change in the devil's status reflects the real possibility that this iconic species could face extinction in the wild within 20 years’.

DFTD is one of only two known cancers that are contagious. It spreads like a cold or flu from animal to animal. The disease is passed when one devil bites another. As the name implies, the disease occurs only in Tasmanian devils and cannot be passed to humans.

When the meat-eating marsupial is infected with DFTD, large tumours develop around its mouth and neck. These growths make it impossible for the devil to eat. Many ultimately die from starvation within six months of being infected.

Julie, my middle daughter, and I had made a plan to visit Tasmania together. Julie has several nursing friends who had suggested that she might be interested in visiting the hospitals in Tasmania. I’d never been there so thought it would be a good idea to ask if I could join her on her travels.

And so it was that she set out from Auckland and I travelled from Wellington to meet in Sydney (arriving half an hour apart!) and we boarded a plane together, bound for Hobart, Tasmania where even more native animals were there to welcome us. What an adventure lay ahead.

And so it was that she set out from Auckland and I travelled from Wellington to meet in Sydney (arriving half an hour apart!) and we boarded a plane together, bound for Hobart, Tasmania where even more native animals were there to welcome us. What an adventure lay ahead.

We arrived at 9.30 in the evening to be met by a very old friend from my squash playing days in the 1980s. He’s been a resident of Hobart for over 30 years and very kindly and generously suggested that he would ‘drive us around’ so that we didn’t waste time getting lost and missing things that were worth seeing. We checked in to our hotel and were very glad to get a really good night’s sleep.

Traffic is heavy in the mornings, as in any major city in the world, so Bill told us to be ready at 8.15 for Julie’s 9.30 am appointment with the Nurse Unit Manager and a Charge Nurse at Royal Hobart Hospital. Bill and I spent over an hour, catching up over a cup of coffee and Julie came back, reporting that she’d had a very worthwhile and informative discussion, had to change into scrubs for part of the meeting and had enjoyed the experience enormously. She was clearly impressed with what she saw which was great to hear.

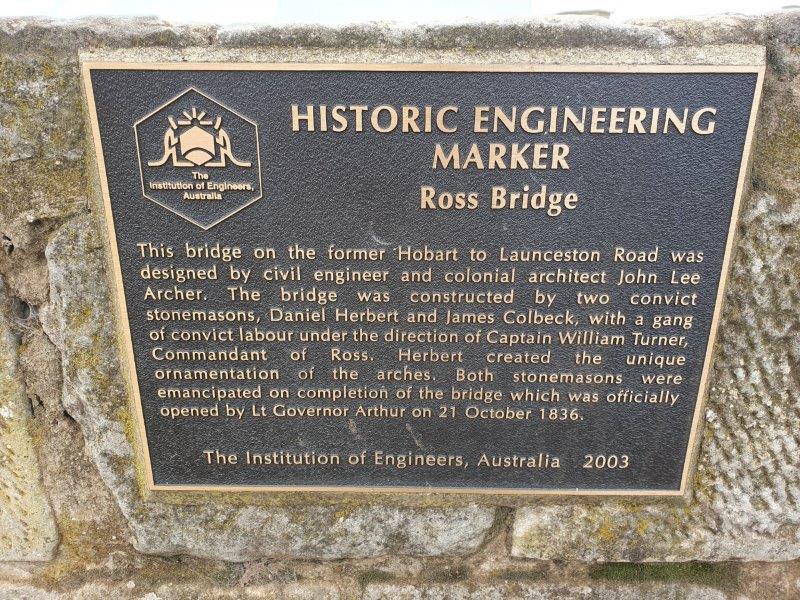

We drove through North Hobart and set out for Launceston, stopping at Ross for lunch. Ross is about 120 north of Hobart and 80km south of Launceston. It’s an historic town in the midlands of Tasmania, situated on the Macquarie River. It’s listed on the Register of the National Estate and is famous for its historic bridge, original sandstone buildings and convict history.

We drove through North Hobart and set out for Launceston, stopping at Ross for lunch. Ross is about 120 north of Hobart and 80km south of Launceston. It’s an historic town in the midlands of Tasmania, situated on the Macquarie River. It’s listed on the Register of the National Estate and is famous for its historic bridge, original sandstone buildings and convict history.

Ross lies in lands that were traditionally owned by Tasmanian Aborigines. The first European to explore the district was a surveyor called Charles Grimes, who passed through the area while mapping Tasmania’s central area, including parts of what later became known as the Macquarie River. Governor Lachlan Macquarie passed through the area himself and, as he recorded in his journal at the time, ‘I named our last night’s station ‘Ross’ in honour of H M Buchanan – that being the name of his seat on Loch Lomond in Scotland. This part of Argyle Plains on the right bank of the Macquarie River being very beautiful and commanding a noble view’.

Ross lies in lands that were traditionally owned by Tasmanian Aborigines. The first European to explore the district was a surveyor called Charles Grimes, who passed through the area while mapping Tasmania’s central area, including parts of what later became known as the Macquarie River. Governor Lachlan Macquarie passed through the area himself and, as he recorded in his journal at the time, ‘I named our last night’s station ‘Ross’ in honour of H M Buchanan – that being the name of his seat on Loch Lomond in Scotland. This part of Argyle Plains on the right bank of the Macquarie River being very beautiful and commanding a noble view’.

The well-known sandstone bridge was constructed by convict labour in 1836, and is the third oldest bridge still in use in Australia. Two stonemasons were employed, James Colbneck and Daniel Herbert, the latter being credited with the intricate carvings along both sides of the bridge.

We drove on to Launceston, past the beautiful Tamar River, found the LGH Hospital to confirm a possible appointment for Julie for first thing the following morning. We found some accommodation very close by to cope with the early start. It wasn’t the best so I won’t recommend it here!

We drove on to Launceston, past the beautiful Tamar River, found the LGH Hospital to confirm a possible appointment for Julie for first thing the following morning. We found some accommodation very close by to cope with the early start. It wasn’t the best so I won’t recommend it here!

Early on Wednesday morning, Julie had an email from the Theatre Manager, Ross, who wanted to meet her at 1.30 so we needn’t have stayed at the somewhat unsatisfactory accommodation the night before. However, it gave us time to walk to the Arora Café just one block up the road for a lovely breakfast of eggs and bacon. As there was still time to spare, Bill drove us to the University of Launceston to visit the nursing school and the Support Service Centre so that Julie could enquire about possible study to coincide with a nursing job if one becomes available.

We didn’t linger in Launceston as Bill had plans for us to travel widely on our way back to Hobart three days later so we didn’t get a really good feel for the city!

We didn’t linger in Launceston as Bill had plans for us to travel widely on our way back to Hobart three days later so we didn’t get a really good feel for the city!

We made our way to Devonport where we saw the Spirit of Tasmania ferry at the quayside. Devonport is the southern terminus for the ferries – Spirit I and II – which travel the 11 hours to Melbourne.

In the early days, coal was an export product from this area which has rich red soils that are ideal for producing vegetable crops (beans, onions, peas, potatoes etc.) and very significant cereals, oil poppies, pyrethrum and other crops.

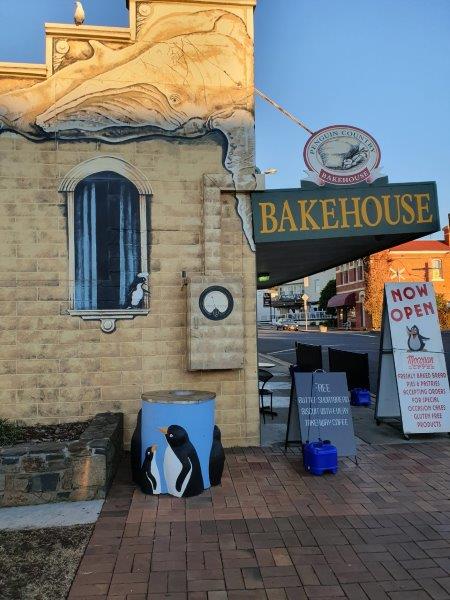

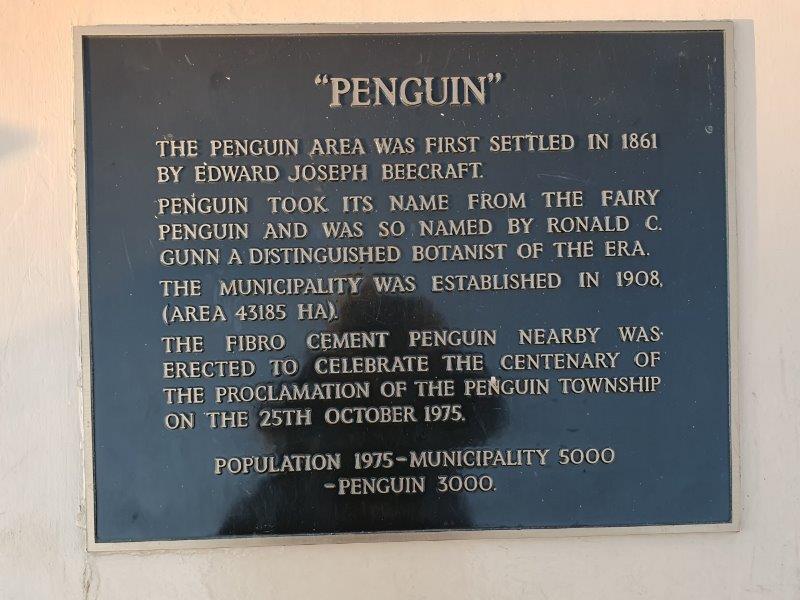

We still had quite a distance to drive so we moved on to the little town of Penguin for coffee and photos. Wherever we looked there were penguins which were very cute!

We still had quite a distance to drive so we moved on to the little town of Penguin for coffee and photos. Wherever we looked there were penguins which were very cute!

Penguin was first settled in 1861 as a timber town, and proclaimed on 25 October 1875. The area's dense bushland and easy access to the sea led to Penguin becoming a significant port town, with large quantities of timber being shipped across Bass Strait to Victoria where the 1850s gold rushes were taking place.

Penguin was first settled in 1861 as a timber town, and proclaimed on 25 October 1875. The area's dense bushland and easy access to the sea led to Penguin becoming a significant port town, with large quantities of timber being shipped across Bass Strait to Victoria where the 1850s gold rushes were taking place.

The town was named by the botanist Ronald Campbell Gunn for the little penguin rookeries that are common along the less populated areas of the coast. Penguin was one of the last districts settled

The town was named by the botanist Ronald Campbell Gunn for the little penguin rookeries that are common along the less populated areas of the coast. Penguin was one of the last districts settled  along the North West coast of Tasmania, possibly because of an absence of a river, for safe anchorage. Nearly all travel in those days was by boat as the bush made the land almost impenetrable. Many of the settlers probably emigrated from Liverpool before landing in Launceston then sailing west along the coast. Trade began when the wharf was built in 1870, allowing timber and potatoes to be exported. Penguin Silver Mine, along the foreshore slightly to the east of the town opened in 1870 but failed a year later.

along the North West coast of Tasmania, possibly because of an absence of a river, for safe anchorage. Nearly all travel in those days was by boat as the bush made the land almost impenetrable. Many of the settlers probably emigrated from Liverpool before landing in Launceston then sailing west along the coast. Trade began when the wharf was built in 1870, allowing timber and potatoes to be exported. Penguin Silver Mine, along the foreshore slightly to the east of the town opened in 1870 but failed a year later.

Leaving the penguins behind, we drove on to the town of Burnie having checked in first to our accommodation in the hills above the town. Blueberry B&B was delightfully rural with beautiful views over the sea below.

Leaving the penguins behind, we drove on to the town of Burnie having checked in first to our accommodation in the hills above the town. Blueberry B&B was delightfully rural with beautiful views over the sea below.

The property is very special and, because of the regular rainfall and good soil, the owners are able to follow permaculture principles and grow many temperate climate flowers, fruits, berries, nuts, herbs and vegetables which  they share with their guests depending what is in season. November is strawberries, December is raspberries, January is great for blueberries, February is apricots and nectarines, March is apple time. April is kiwi fruit, and so it goes.

they share with their guests depending what is in season. November is strawberries, December is raspberries, January is great for blueberries, February is apricots and nectarines, March is apple time. April is kiwi fruit, and so it goes.

They obviously care about being environmentally aware, so artificial chemicals are not used, not even Roundup. We were told that many things are recycled, cardboard and wood chips for mulch, and horse and chicken manure to fertilize, as well as having their own compost and worm farm.  They nearly always have fresh flowers for their guests, in the summer, roses, in autumn dahlias A large vase of alstroemerias awaited us as proof of this.

They nearly always have fresh flowers for their guests, in the summer, roses, in autumn dahlias A large vase of alstroemerias awaited us as proof of this.

We were greeted warmly by our hosts and told that the whole house was ours and that if we made a note of what we would like for breakfast, it would be brought to us at the time we chose the next morning! We couldn’t ask for more, so leaving our ‘home’ we set off back down the hill for a lovely dinner at the Beach Hotel in Burnie before retiring home again for an early night after the long drive.

We were greeted warmly by our hosts and told that the whole house was ours and that if we made a note of what we would like for breakfast, it would be brought to us at the time we chose the next morning! We couldn’t ask for more, so leaving our ‘home’ we set off back down the hill for a lovely dinner at the Beach Hotel in Burnie before retiring home again for an early night after the long drive.

Before we left the area we dipped down into Burnie, a lovely town. It’s a port city on the north-west coast. When founded in 1827, Burnie was named Emu Bay but it was renamed for William Burnie, a director of the Van Diemen’s Land Company in the early 1840s. It was proclaimed a city by Queen Elizabeth II on April 26, 1988. The key industries are heavy manufacturing, forestry and farming. The Burnie port along with the forestry industry provides the main source of revenue for the city. Burnie was the main port for the west coast mines after the opening of the Emu Bay Railway in 1897. Most industry in Burnie was based around the railway and the port that served it.

The agriculture industry has largely been replaced by forestry which has had a major role in Burnie's development in the 1900s with the founding of the pulp and paper mill by Associated Pulp and Paper Mills in 1938 and the woodchip terminal in the latter part of the century. The Burnie Paper Mill closed in 2010 after failing to secure a buyer. Burnie Port is Tasmania's largest general cargo port and was once Australia's fifth largest container port. It is the nearest Tasmanian port to Melbourne and the Australian mainland. It currently operates as a container port with a separate terminal for the exportation of woodchips.

Leaving Burnie, we drove south-west on country roads for some distance until we suddenly came upon the Tullah Lakeside Lodge in the middle of nowhere and stopped for some hot chocolate for morning tea.

Leaving Burnie, we drove south-west on country roads for some distance until we suddenly came upon the Tullah Lakeside Lodge in the middle of nowhere and stopped for some hot chocolate for morning tea.

Situated on the banks of a beautiful trout-filled lake in the middle of ancient rain forest, this would have been a beautiful place at which to have stayed a night. Remarkably they told us that the rooms are rented out at only AUD100 a night which was cheaper than most of the accommodation we found elsewhere. The Lodge is surrounded by 'moody' mountains, Farrell and Muchison and they told us that it’s a photographer’s paradise as the reflections on the lake are rippled by waterbirds, fish and platypus.

Situated on the banks of a beautiful trout-filled lake in the middle of ancient rain forest, this would have been a beautiful place at which to have stayed a night. Remarkably they told us that the rooms are rented out at only AUD100 a night which was cheaper than most of the accommodation we found elsewhere. The Lodge is surrounded by 'moody' mountains, Farrell and Muchison and they told us that it’s a photographer’s paradise as the reflections on the lake are rippled by waterbirds, fish and platypus.

It was hard to drag ourselves away but there was still a big distance to cover so Bill drove us on to Strahan (pronounced "straw-n"), a small town and former port on the west coast, now a significant locality for tourism in the region. Strahan Harbour and Risby Cove form part of the north-east end of Long Bay on the northern end of Macquarie Harbour.

It was hard to drag ourselves away but there was still a big distance to cover so Bill drove us on to Strahan (pronounced "straw-n"), a small town and former port on the west coast, now a significant locality for tourism in the region. Strahan Harbour and Risby Cove form part of the north-east end of Long Bay on the northern end of Macquarie Harbour.

Originally developed as a port of access for the mining settlements in the area, the town was known as Long Bay or Regatta Point until 1877, when it was formally named after the colony’s Governor, Sir George Cumine Strahan. Strahan was a vital location for the timber industry that existed around Macquarie Harbour.

For a substantial part of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it also was port for regular shipping of passengers and cargo. The Strahan Marine Board was an important authority dealing with the issues of the port and Macquarie Harbour up until the end of the twentieth century when it was absorbed into the Hobart Marine Board.

The northern shore of Macquarie Harbour is across the bay from Regatta Point, the terminus of the recently reconstructed, West Coast Wilderness Railway which runs northwards from Strahan alongside the Queen River and the northern slopes of the King River to its eastern terminus of Queenstown. Bill had thought that Julie and I could take the train while he drove to Queenstown to meet us but unfortunately the train doesn’t run on a Thursday so we all drove the distance together.

The northern shore of Macquarie Harbour is across the bay from Regatta Point, the terminus of the recently reconstructed, West Coast Wilderness Railway which runs northwards from Strahan alongside the Queen River and the northern slopes of the King River to its eastern terminus of Queenstown. Bill had thought that Julie and I could take the train while he drove to Queenstown to meet us but unfortunately the train doesn’t run on a Thursday so we all drove the distance together.

Queenstown's history has long been tied to the mining industry. This mountainous area was first explored in 1862 and it was long after that when alluvial gold was discovered at Mount Lyall, prompting the formation of the Mount Lyall Gold Mining Company in 1881. Exploration continues within the West Coast region for further economic mineral deposits, and due to the complexity of the geology, there is always the possibility that new mines will open. The Henty Gold Mine which commenced operation in the 1990s is a good example of this.

Unfortunately we spent a little too long in Queenstown and even visited the Museum which we thought would give us some information about the mining industry in the area. But it actually covered everything about the area and was too general to make much sense of in such a short space of time. We hadn’t realized that Bill had another thought in his mind, that of taking us to visit The Wall at Derwent Bridge, a ninety-minute drive away, and we’d have been better placed to have missed out the Museum altogether because we didn’t make Derwent Bridge before The Wall closed.

The Wall is an inspirational tale carved from the mountains and rivers of the Central Highlands. An artist called Greg Duncan has been creating a stunning sculpture at Derwent Bridge in the heart of Tasmania. ‘The Wall in the Wilderness’ is Greg Duncan’s commemoration of those who helped shape the past and present of Tasmania’s central highlands.

The Wall is an inspirational tale carved from the mountains and rivers of the Central Highlands. An artist called Greg Duncan has been creating a stunning sculpture at Derwent Bridge in the heart of Tasmania. ‘The Wall in the Wilderness’ is Greg Duncan’s commemoration of those who helped shape the past and present of Tasmania’s central highlands.

Although we didn’t actually get to see it, it’s a work in progress, carved from three-metre high wooden panels. The carved panels tell the history of the harsh Central Highlands region, beginning with the indigenous people, then to the pioneering timber harvesters, pastoralists, miners and hydro workers. When completed, The Wall will be 100 metres long and Greg Duncan’s sculpture will rank as a major work of art and tourist attraction in Tasmania.

Julie and I had been having difficulty organizing accommodation through this part of Tasmania. The next stop we’d arranged was the strangest experience we’ve ever had. We imagined that Tarraleah would be some sort of a township with perhaps a hotel and some shops but, in fact, it turned out to be a turning to the north off the main road saying ‘Taraleah 1km’. The road led to a collection of houses around a large grassed area in the middle of nowhere. The 1km road was seriously in need of maintenance with huge potholes and we wondered where we were going to. It was almost dark when we arrived but we managed to find a construction worker who told us that we were, in fact, in the right place. We asked him where we could go for dinner and he said cheerfully ‘Hobart’ (about two hours away!). However, he said that Matthew, the manager of the estate, would see us right and told us where to find him!

Matthew, when we found him said he could sell us some frozen meals and he showed us to our accommodation where we enjoyed the warmth of the large house (the one in the middle) with three bedrooms, two bathrooms and a large lounge with a TV. We had never experienced anything quite like it before, a township of delightful cottages built around a square but without any amenities at all. There is a café on the estate that is open throughout the summer months but we’d obviously arrived too late to find that operating.

Matthew, when we found him said he could sell us some frozen meals and he showed us to our accommodation where we enjoyed the warmth of the large house (the one in the middle) with three bedrooms, two bathrooms and a large lounge with a TV. We had never experienced anything quite like it before, a township of delightful cottages built around a square but without any amenities at all. There is a café on the estate that is open throughout the summer months but we’d obviously arrived too late to find that operating.

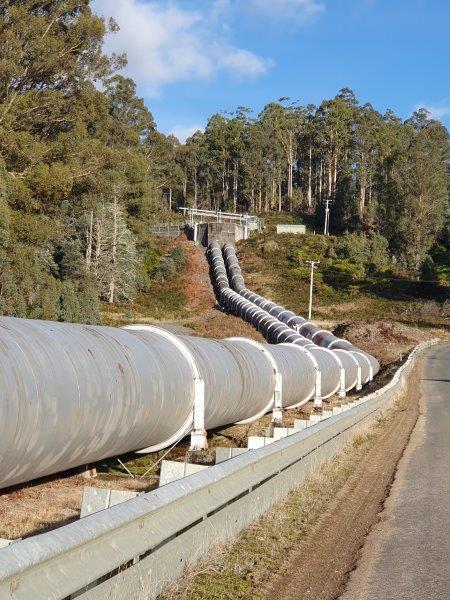

We discovered that Tarraleah is described as a small town in the Central Highlands about 125 km north-west of Hobart. The township was built in the 1930s by the Hydro Electric Commission to house Tasmania's pioneering hydro-electricity officers and management. The Post Office there opened on 11 October 1934, and the township was named Tarraleah in 1935.

We discovered that Tarraleah is described as a small town in the Central Highlands about 125 km north-west of Hobart. The township was built in the 1930s by the Hydro Electric Commission to house Tasmania's pioneering hydro-electricity officers and management. The Post Office there opened on 11 October 1934, and the township was named Tarraleah in 1935.

The area is noted for its alpine lakes and mountains, and many hydro-electric dams, canals and giant steel pipeways. It’s located along the Lyell Highway, and is only a short distance from both Lake King William and Bronte Lagoon. Lake Lipootah and Bradys Lake are also close by.

After a multi-million-dollar redevelopment, the former Hydro construction 'village' has become an estate that comprises Tarraleah Lodge with accommodation, recreation, and dining options. Freshwater trout fishing, boating, bushwalking, mountain biking and kayaking are all popular activities in and around the township. Tarraleah is also home to a high altitude golf course.

After a multi-million-dollar redevelopment, the former Hydro construction 'village' has become an estate that comprises Tarraleah Lodge with accommodation, recreation, and dining options. Freshwater trout fishing, boating, bushwalking, mountain biking and kayaking are all popular activities in and around the township. Tarraleah is also home to a high altitude golf course.

In 1914, the State Government set up the Hydro-Electric Department (changed to the Hydro-Electric Commission in 1929) to complete the first HEC power station, the Waddamana Hydro-Electric Power Station. Prior to that, two private hydro-electric stations had been opened. The Launceston City Council’s Duck Reach Power Station opened in 1895 on the South Esk River (it was one of the first hydrelectric power stations in the southern hemisphere). Reefton in New Zealand is the first municipal hydro-station, beginning operations in 1888) and the Mount Lyell Mining and Railway Company’s Lake Margaret Power Station, opened in 1914. Both these power stations were taken over by the HEC and closed in 1955 and 2006 respectively.

Following the Second World War in the 1940s and early 1950s, many migrants came to Tasmania to work for the HEC with construction of dams and sub-stations. This was similar to the Snowy Mountains Scheme in New South Wales and had similar effects in bringing a significant number of people into the local community, enriching the social fabric and culture of each state. Most constructions in this era were concentrated in the centre of the island.

As the choice of rivers and catchments in the central highlands were exhausted, the planners and engineers began serious surveying of the rivers of the west and south-west regions of the state. The long term vision of those within the HEC and the politicians in support of the process, was for continued use of all of the state's water resources.

As a consequence of such a vision, the politicians and HEC bureaucrats were able to create the upper Gordon river power development schemes despite worldwide dismay at the loss of the original Lake Pedder. The hydro-industrialisation of Tasmania was seen as paramount above all, and the complaints from outsiders were treated with disdain.

After a very pleasant and comfortable night, Julie and I went out to see the birds being fed at 8.00 and tried unsuccessfully to find the highland cattle that Matthew had told us were on the Estate, to take photos to send to Suzi. It was also the first opportunity I

After a very pleasant and comfortable night, Julie and I went out to see the birds being fed at 8.00 and tried unsuccessfully to find the highland cattle that Matthew had told us were on the Estate, to take photos to send to Suzi. It was also the first opportunity I  had to take a photo of one of the trees showing the changing colours of the leaves that were evident all over the country. This was probably the biggest difference in the landscape between New Zealand and Tasmania – the large numbers of deciduous trees, particularly eucalyptus which made the landscape very colourful.

had to take a photo of one of the trees showing the changing colours of the leaves that were evident all over the country. This was probably the biggest difference in the landscape between New Zealand and Tasmania – the large numbers of deciduous trees, particularly eucalyptus which made the landscape very colourful.

As there was no café on the estate or anywhere even faintly close by, we started the 40-minute drive to a very small town called Hamilton where we found Fennel Café and had a lovely breakfast of eggs and bacon.

As there was no café on the estate or anywhere even faintly close by, we started the 40-minute drive to a very small town called Hamilton where we found Fennel Café and had a lovely breakfast of eggs and bacon.

This area, in particular, has large numbers of cattle, both for meat and milk so it was great to see a lovely milking herd in a paddock nearby. As you can tell, this photo might just as easily have been taken in New Zealand!

This area, in particular, has large numbers of cattle, both for meat and milk so it was great to see a lovely milking herd in a paddock nearby. As you can tell, this photo might just as easily have been taken in New Zealand!

Leaving Hamilton, Bill drove us straight on towards Hobart, stopping so that we could take a photo of the bridge at New Norfolk, hidden behind the autumn foliage.

New Norfolk is a town on the Derwent River, about 20 kms north-west of Hobart, still on the Lyell Highway with a population of just over 5,000. It's a modern Australian regional centre which retains evidence of its pioneer heritage.

New Norfolk is a town on the Derwent River, about 20 kms north-west of Hobart, still on the Lyell Highway with a population of just over 5,000. It's a modern Australian regional centre which retains evidence of its pioneer heritage.

Two examples of this heritage are Tasmania's oldest Anglican church, St. Matthews (built in 1823) and one of Australia's oldest hotels, the Bush Inn (Tasmania), trading continuously in the same building (built in 1815). Many private homes from the 1820s have also survived and look down on the beautiful river with the colourful autumn trees in evidence as we passed through.

From here it was only a hop, skip and a jump (as they say) to Sandy Bay in Hobart to visit the University of Tasmania so that Julie could find out some more from the recruitment team and support services about any possible future studying she could do while working. She’d read that future study of this kind was possible in Hobart but it turned out to be more complicated than she’d thought.

It was still morning and Bill suggested that we drive up to the top of Mount Nelson as the sky was clear and we would get a good view.

It was still morning and Bill suggested that we drive up to the top of Mount Nelson as the sky was clear and we would get a good view.

Mount Nelson was originally named 'Nelson's Hill' by Captain William Bligh (of Mutiny on the Bounty fame) in 1792 in honour of David Nelson, the botanist of the Bounty mission, as "he was the first white man on it" when the Bounty visited ‘Van Diemens Land’ on its way to Tahiti. Nelson was one of the Bounty crew who was loyal to Bligh during the mutiny. He died at Kupang in Timor on 20 July 1789 of an 'inflammatory fever' caused by the long open-boat voyage following the mutiny. His funeral was attended by the Governor and officers from every ship in the harbour. The name 'Nelson's Hill' was later changed to Mount Nelson.

When Governor Lachlan Macquarie visited Van Diemen's Land in 1811, he directed that a signal post should be established on the summit of Mount Nelson to announce the appearance of all ships entering the estuary. The semaphore technology of the signal station was superseded when Tasmania's first telephone line was established between the Mount Nelson signal station and the Hobart telegraph office in 1880. Most of the modern suburban development in Mount Nelson has taken place since 1945 when the government encouraged settlement of immigrants escaping the destruction that took place in Europe after World War II. During this same period the section of hill face north of the bends on Nelson Road, which used to be a firing range, was converted into university farmland for the University of Tasmania.

When Governor Lachlan Macquarie visited Van Diemen's Land in 1811, he directed that a signal post should be established on the summit of Mount Nelson to announce the appearance of all ships entering the estuary. The semaphore technology of the signal station was superseded when Tasmania's first telephone line was established between the Mount Nelson signal station and the Hobart telegraph office in 1880. Most of the modern suburban development in Mount Nelson has taken place since 1945 when the government encouraged settlement of immigrants escaping the destruction that took place in Europe after World War II. During this same period the section of hill face north of the bends on Nelson Road, which used to be a firing range, was converted into university farmland for the University of Tasmania.

From the top of Mount Nelson we took photos of the surrounding countryside and the city of Hobart resting with the ocean on all sides – a very picturesque site.

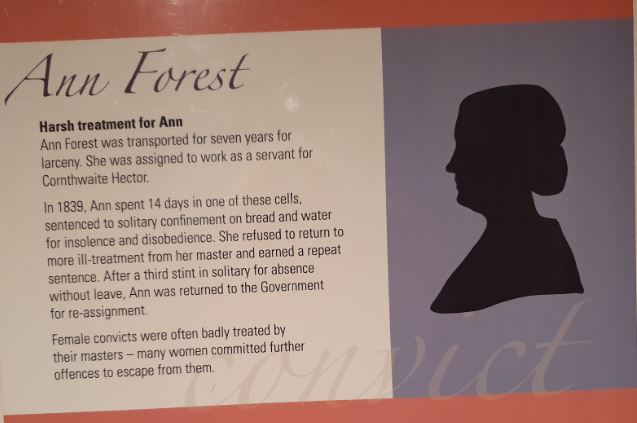

Coming down to sea level again, we thought we’d visit the Cascades Female Factory which friends had recommended as being worth a visit. It was, as they said, sobering but perhaps not quite as sobering as the men’s goal which we visited a few hours later.

The Cascades Female Factory was a former Australian workhouse for female convicts in the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Lane. Operational between 1828 and 1856, the factory is now one of the 11 sites that collectively comprise the Australian Convict Sites, listed on the World Heritage List by UNESCO. It was inscribed on the World Heritage list in July 2010, along with ten other Australian convict sites.

The Cascades Female Factory was a former Australian workhouse for female convicts in the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Lane. Operational between 1828 and 1856, the factory is now one of the 11 sites that collectively comprise the Australian Convict Sites, listed on the World Heritage List by UNESCO. It was inscribed on the World Heritage list in July 2010, along with ten other Australian convict sites.

Collectively the Australian Convict Sites represent an exceptional example of the forced migration of convicts and an extraordinary example of global developments associated with punishment and reform. Representing the female experience, the Cascades Female Factory demonstrates how penal transportation was used to expand Britain's spheres of influence, as well as to punish and reform female convicts.

Now operational as a museum and tourist attraction, the site is managed by the Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority.

Some rooms in the Macquarie Street Goal served as a temporary Hobart "Female Factory" in the mid-1820s. The Cascades Female Factory was purpose-built in 1828 and was intended to remove women convicts from the negative influences and temptations of Hobart, and also to protect society from what was seen as their immorality and corrupting influence. The Factory was located, however, in an area of damp swampland, and with overcrowding, poor sanitation and inadequate food and clothes, there was a high rate of disease and mortality among its inmates.

The Cascades Female Factory is the only remaining female factory with extant remains which give a sense of what female factories were like. Today the Cascades Female Factory Historic Site consists of three of the original five yards. It is open every day (except Christmas) and offers a range of tours.

One of the most interesting parts of the day was a visit to Richmond – definitely an area not to be missed and full of history.

It is a town about 25 km north-east of Hobart, in the Coal River region, between the Midland Highway and Tasman Highway with a population of under 1,000. Despite how small it is, it’s brimming with interest.

Richmond's most famous landmark is the Richmond Bridge, built in 1823-1825, around the time of the town's first settlement using convict labour, and is known as the largest stone span bridge in Australia. It is Australia's oldest bridge still in use. Julie and I walked over it and took lots of photos – too many to post here – because we found it very engaging.

Richmond's most famous landmark is the Richmond Bridge, built in 1823-1825, around the time of the town's first settlement using convict labour, and is known as the largest stone span bridge in Australia. It is Australia's oldest bridge still in use. Julie and I walked over it and took lots of photos – too many to post here – because we found it very engaging.

St John's Catholic church was built in 1836, and is considered the oldest Roman Catholic church in Australia.

The town was initially part of the route between Hobart and Port Arthur until the Sorell – which we crossed the following day - was constructed in 1872.

Present-day Richmond is best known as being preserved as it was at that time. It is a vibrant tourist town, with many of the sandstone structures still standing. Many of these structures are built in the Georgian style – one of my favourite architectural styles which is probably why I found it so attractive.

The name given to the region was the Coal River district. Lieutenant-governor William Sorell was the first to take steps to form a town and later he took up land there himself. The Land Commissioners surveyed land for a township in the mid-1820s.

James Backhouse reported Richmond had a courthouse, a gaol, a windmill and about thirty houses by 1832. Backhouse visited the town again in February 1834 and reported Richmond had nearly doubled in size. The courthouse was built in 1825-26 and the northern part of the gaol in 1825. Richmond Post Office opened on 1 June 1832.

The Richmond Gaol was fascinating. It’s a convict era building and now a tourist attraction, and is the oldest intact gaol in Australia. Building of the gaol started in 1825, and predates the establishment of the penal colony at Port Arthur in 1833. One of the tasks completed by the convicts who were held at Richmond Gaol was the construction of Richmond Bridge.

Most of the gaol buildings have not been changed since convict times. They include an example of a female solitary confinement cell, measuring 2 metres (6.6 ft) by 1 metre (3.3 ft).

Most of the gaol buildings have not been changed since convict times. They include an example of a female solitary confinement cell, measuring 2 metres (6.6 ft) by 1 metre (3.3 ft).

The buildings include a chain gang sleeping rooms, a flogging yard, a cookhouse and holding rooms. The buildings also feature historical relics and documents. Punishment cells were places of punishment where prisoners wore heavy leg irons.

The buildings include a chain gang sleeping rooms, a flogging yard, a cookhouse and holding rooms. The buildings also feature historical relics and documents. Punishment cells were places of punishment where prisoners wore heavy leg irons.

By the 1830s, the gaol was horribly overcrowded because of it being so small - 19 square metres - and prisoners were forced to sleep in the passageways.

The two storey building began construction in 1832 and was completed in 1833. The upper level served as the Gaoler's Residence with the downstairs section being storage.

In 1835, the Eastern and Western wings were added and it's the Western Wing serves as the entrance to the building to this very day. Once these were completed it created better segregation between male and female prisoners. The female wing contained a new cookhouse and bake oven.

In an attempt to negate the escapes and escape attempts from the gaol, it was surrounded with a stone wall. This was erected in 1840.

By the mid-1850s, the place was only being used as a Watch House due to the cessation of convict transportation. In 1861, it was controlled by the municipal police and when they were removed to become centralised in Hobart, the gaol simply became a group of holding cells.

By the mid-1850s, the place was only being used as a Watch House due to the cessation of convict transportation. In 1861, it was controlled by the municipal police and when they were removed to become centralised in Hobart, the gaol simply became a group of holding cells.

By the end of the 1920s, it was abandoned.

In 1945, the gaol was rescued by becoming a State Reserve and through legislation in the 1970s, it was run by the National Parks and Wildlife Service, meaning that the gaol could be classified as an historic site under their control. At the end of this somewhat traumatic experience we were glad to return to our hotel for an early night!

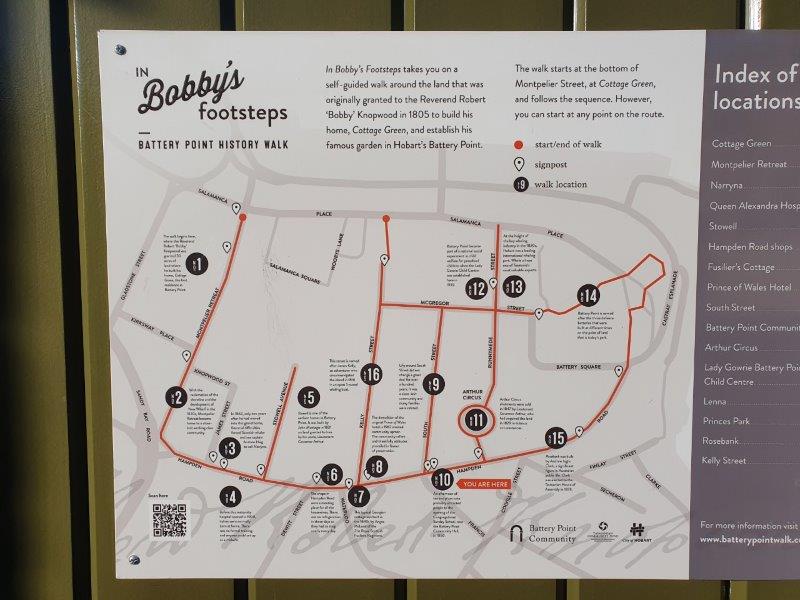

Saturday was our opportunity to visit Battery Point and walk through the Salamanca Place market about which we’d heard great things! Bill dropped us off in the middle of the historic Battery Point and picked us up again seven hours later after we’d spent an amazing day strolling through parts of the city near the waterfront.

Battery Point is a suburb of the city immediately south of the central business district. It’s in the local government area of Hobart.

Battery Point is a suburb of the city immediately south of the central business district. It’s in the local government area of Hobart.

It’s named after the battery of guns which were established on the point in 1818 as part of the Hobart coastal defences. The battery was situated on the site of today's Princes Park. The guns were used to fire salutes on ceremonial occasions but were never called upon to repel an invasion. The battery was decommissioned after an 1878 review of Hobart's defences found that its location would tend to draw an enemy's fire onto the surrounding residential neighbourhood. The site was subsequently handed over to the Hobart City Council as a place of recreation and amusement. When the Council carried out works to beautify the park in 1934, they discovered underground tunnels which had served as a magazine for the original battery.

The area is generally known as one of the city's more prestigious suburbs, with many large and extravagant homes and apartment blocks. It has a large number of historic houses dating from the first European settlement of Hobart Town. Battery Point residents have been the centre of controversy in recent years, demanding noise restrictions and other measures aimed at safeguarding a sheltered lifestyle. It adjoins the waterfront Salamanca area as well as the nearby prestigious suburb of Sandy Bay.

The area is generally known as one of the city's more prestigious suburbs, with many large and extravagant homes and apartment blocks. It has a large number of historic houses dating from the first European settlement of Hobart Town. Battery Point residents have been the centre of controversy in recent years, demanding noise restrictions and other measures aimed at safeguarding a sheltered lifestyle. It adjoins the waterfront Salamanca area as well as the nearby prestigious suburb of Sandy Bay.

Probably the most significant part of this historic area is Arthur Circus with its cottages, mostly originally constructed for the officers of the garrison.

Joining Battery Point to Salamanca Place are some steps called Kelly Street steps and we made our way down these to Salamanca Place.

Joining Battery Point to Salamanca Place are some steps called Kelly Street steps and we made our way down these to Salamanca Place.

Salamanca Place consists of rows of sandstone buildings, formerly warehouses for the port of Hobart Town that have since been converted into restaurants, galleries, craft shops and offices. It was named after the victory in 1812 of the Duke of Wellington in the Battle of Salamanca in the Spanish province of Salamanca. It was previously called "The Cottage Green".

Each Saturday, Salamanca Place is the site for the Salamanca Market, which is popular with tourists and locals. The markets are ranked as one of the most popular tourist attractions visited each year and we spent over an hour strolling through all the stalls. It was so absorbing that I completely forgot to take many photos but I did manage to be tempted by a lovely leather handbag and a cashmere scarf (having left mine in New Zealand and finding it cold!)

Each Saturday, Salamanca Place is the site for the Salamanca Market, which is popular with tourists and locals. The markets are ranked as one of the most popular tourist attractions visited each year and we spent over an hour strolling through all the stalls. It was so absorbing that I completely forgot to take many photos but I did manage to be tempted by a lovely leather handbag and a cashmere scarf (having left mine in New Zealand and finding it cold!)

Salamanca Place is also popular after dark with both locals and visitors enjoying bars and eateries located there and the nearby wharves.

In the mid-1990s, Salamanca Square, a sheltered public square was built. Ringed by shops, cafes, and restaurants, the centrepiece fountain and its lawns are a safe environment where children play alongside individuals and families. There is also an adjoining undercover car park and a large apartment complex.

In the mid-1990s, Salamanca Square, a sheltered public square was built. Ringed by shops, cafes, and restaurants, the centrepiece fountain and its lawns are a safe environment where children play alongside individuals and families. There is also an adjoining undercover car park and a large apartment complex.

There are many laneways and several squares adjacent to Salamanca Place, built during the whaling industry boom in the early and mid-19th century. Interestingly, it is featured as a property in the Australian version of Monopoly.

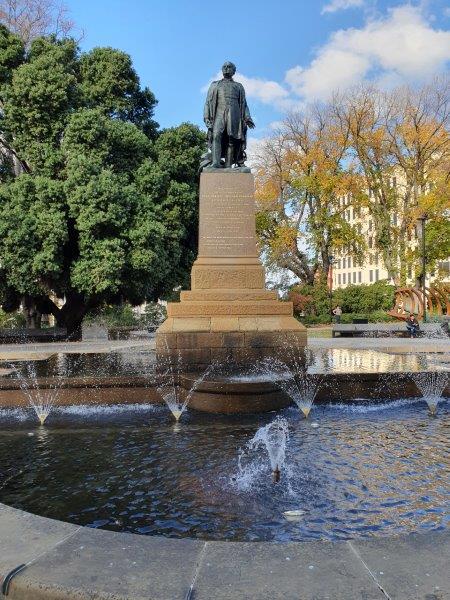

Leaving the market stalls behind us we visited St David’s Cathedral on the corner of Macquarie and Murray Streets. A wedding had just taken place and the wedding party left in two vintage Rolls Royces! Inside, the cathedral was much smaller than it appeared on the outside but it was, of course, very beautiful and peaceful.

Consecrated in 1874, St David's is the Bishop of Tasmania’s principal place of teaching. It is a cathedral because it is the place where the bishop's ‘cathedra’ or seat is placed. It is also the venue for great occasions of diocese, city and state.

Consecrated in 1874, St David's is the Bishop of Tasmania’s principal place of teaching. It is a cathedral because it is the place where the bishop's ‘cathedra’ or seat is placed. It is also the venue for great occasions of diocese, city and state.

We continued our meanderings and made our way through the Cat and Fiddle Mall (where we found that many of the shops were exactly the same as those in Wellington!).The Cat and Fiddle Arcade has been the heart of Hobart shopping for more than 100 years. Today it is the city’s vibrant style capital with more than 70 speciality stores. From great coffee to homewares, with an extraordinary range of fashion, this is Hobart’s style capital.

Somewhat exhausted from a very long walk (so far), we made our way down to the waterfront to seek out a very late lunch and found a great restaurant called Fish Frenzy.

Somewhat exhausted from a very long walk (so far), we made our way down to the waterfront to seek out a very late lunch and found a great restaurant called Fish Frenzy.

We were told that Fish Frenzy is famous for its delicious, daily fresh fish and chips, grilled seafood, salads and amazing hot seafood chowder. We discovered what the locals probably take for granted.

The fast and friendly service was complemented by the incredible waterfront location of the restaurant, overlooking the docks and working port. We decided that every visit to Hobart should include a stop at Fish Frenzy, either to eat there as we did, or take away.

The fast and friendly service was complemented by the incredible waterfront location of the restaurant, overlooking the docks and working port. We decided that every visit to Hobart should include a stop at Fish Frenzy, either to eat there as we did, or take away.

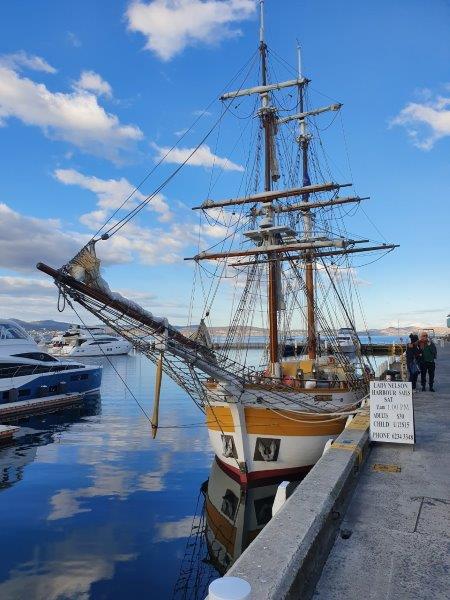

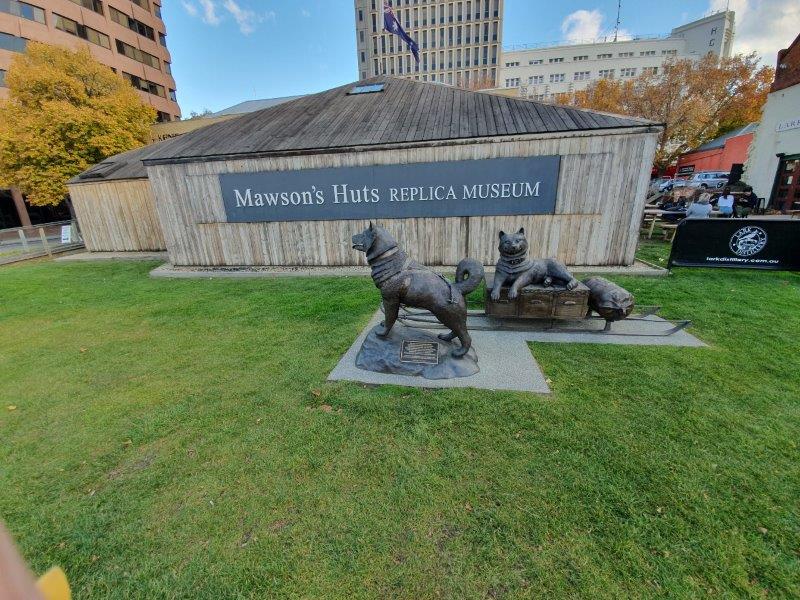

Just a very short walk along the waterfront, we came upon Mawson’s Huts.

Mawson's Huts are the collection of buildings located at Cape Denison, Commonwealth Bay, in the far eastern sector of the Australian Antarctic Territory, some 3000 km south of Hobart. The buildings were erected and occupied by the Australian Antarctic Expedition (AAE) of 1911-1914, led by geologist and explorer Sir Douglas Mawson.

Mawson's Huts are rare as one of just six surviving sites from the Heroic Era of Antarctic exploration. The Australasian Antarctic Expedition was the only Heroic Era expedition organised, manned and supported primarily by Australians.

The huts included a magnetograph hut, used to measure variations in the south magnetic pole, an absolute magnetic hut, which was used as a reference point for studies in the magnetograph hut; and the transit hut, an astronomical observatory. The most important building at the site on Morrison Street in Hobart is the winter living quarters, also known as "Mawson's Hut". This pyramid-roofed hut was home to the eighteen men of the AAE main base party in 1912, and the seven (including Douglas Mawson) who stayed on for an unplanned second year in 1913.

The most important building at the site on Morrison Street in Hobart is the winter living quarters, also known as "Mawson's Hut". This pyramid-roofed hut was home to the eighteen men of the AAE main base party in 1912, and the seven (including Douglas Mawson) who stayed on for an unplanned second year in 1913.

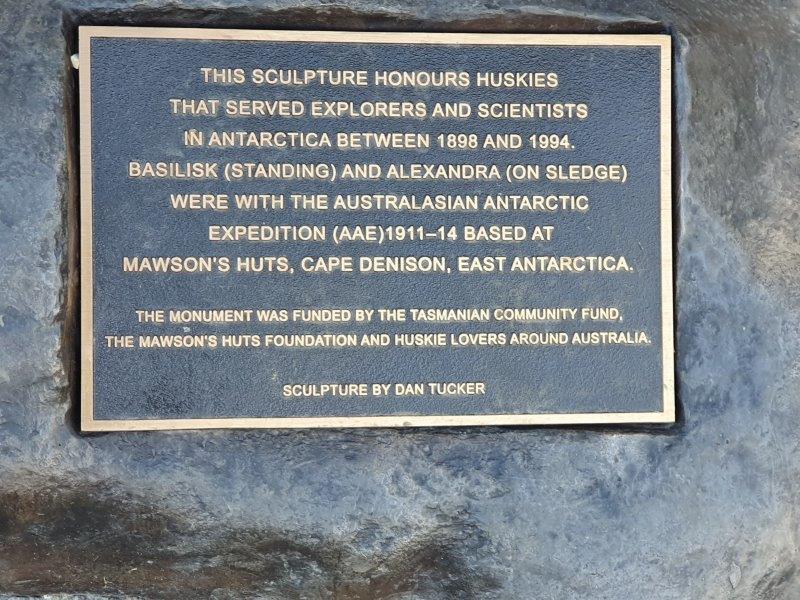

Outside the Huts was this plaque, honouring huskies that served explorers and scientists in Antarctica between 1898 and 1994. Basilisk (standing) and Alexandra (on sledge) were with the Australasian Antarctic Expedition from 1911-1914, based at Cape Denison, East Antarctica.

Outside the Huts was this plaque, honouring huskies that served explorers and scientists in Antarctica between 1898 and 1994. Basilisk (standing) and Alexandra (on sledge) were with the Australasian Antarctic Expedition from 1911-1914, based at Cape Denison, East Antarctica.

The hut combines two sections - the living quarters and the workshop, prefabricated in Sydney and Melbourne respectively, and shipped to the site for construction in 1912 by the AAE team.

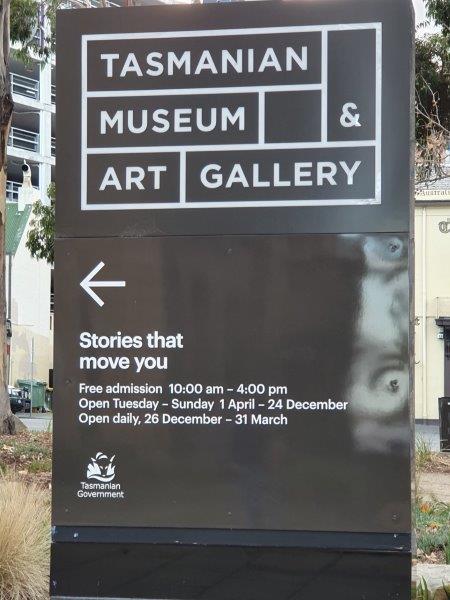

We’d spent so long over the first part of our walking tour that we didn’t have enough time to do justice to the Museums on offer in this part of the city. We only managed to pop our noses into The Maritime Museum but did spend a bit longer in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in which we could have passed many long hours.

We’d spent so long over the first part of our walking tour that we didn’t have enough time to do justice to the Museums on offer in this part of the city. We only managed to pop our noses into The Maritime Museum but did spend a bit longer in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) in which we could have passed many long hours.

The museum was established in 1846, by the Royal Society of Tasmania, the oldest Royal Society outside England. We were told that the TMAG receives 400,000 visitors annually.

We were also told that The Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG) is one of the best places to go when visiting Tasmania with exceptional collections and wonderful exhibitions and we couldn’t agree more!

It is housed in some of the oldest buildings in the state and is the second oldest museum in Australia. It has a rare and unique collection with some objects originating from the country’s oldest scientific society, the Royal Society of Tasmania, which was established in 1843.

TMAG, as locals affectionately know it, is a 'well-loved state museum that visitors of all ages and interests will enjoy'. It has extensive collections and displays including natural history, social history, geology, zoology and maritime history. It is also responsible for the development, maintenance and management of the botanical collections of Tasmania through the Tasmanian Herbarium. The museum is also unique in that it houses an extensive collection of Tasmanian colonial and contemporary art as well as a decorative arts, photography and design.

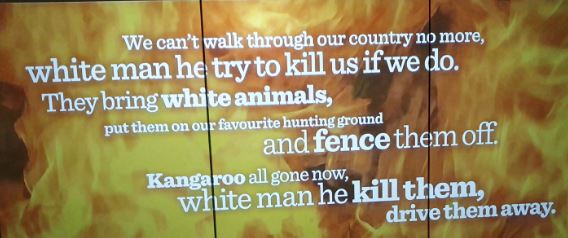

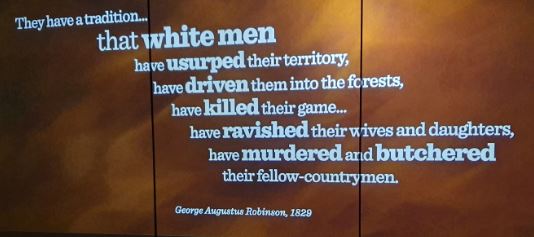

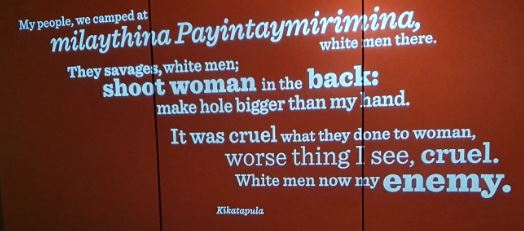

Our land: parrawa, parrawa! Go away! is a permanent exhibition on level 2 of the Bond Store Galleries and is a powerful and immersive journey telling the story of the Aboriginal people and the colonists following the invasion of lutruwita, now called Tasmania, focusing on the Black War. I could have spent hours here, learning about how the indigenous peoples were treated. And it wasn't good ...

Our land: parrawa, parrawa! Go away! is a permanent exhibition on level 2 of the Bond Store Galleries and is a powerful and immersive journey telling the story of the Aboriginal people and the colonists following the invasion of lutruwita, now called Tasmania, focusing on the Black War. I could have spent hours here, learning about how the indigenous peoples were treated. And it wasn't good ...

I spent some time visiting the newly-refreshed ningina tunapri Tasmanian Aboriginal gallery which explores the journey of Tasmanian Aboriginal people and is a celebration of all Tasmanian Aboriginal generations.

I spent some time visiting the newly-refreshed ningina tunapri Tasmanian Aboriginal gallery which explores the journey of Tasmanian Aboriginal people and is a celebration of all Tasmanian Aboriginal generations.

We didn’t get to this part, but we understand that ‘the museum also invites you to journey south from Hobart across the oceans to the frozen continent of Antarctica through its Islands to Ice permanent exhibition. It explores The Power of Change and the social and political changes in twentieth-century Tasmanian life that influenced national and international conversations. Moreover, you can gain a better perspective on the history of The Thylacine: Skinned, Stuffed, Pickled and Persecuted and be reminded how easily a species like the Tasmanian Tiger can be lost’.

We didn’t get to this part, but we understand that ‘the museum also invites you to journey south from Hobart across the oceans to the frozen continent of Antarctica through its Islands to Ice permanent exhibition. It explores The Power of Change and the social and political changes in twentieth-century Tasmanian life that influenced national and international conversations. Moreover, you can gain a better perspective on the history of The Thylacine: Skinned, Stuffed, Pickled and Persecuted and be reminded how easily a species like the Tasmanian Tiger can be lost’.

Best of all, the museum is free to all so you can visit as many times as you like!

We tore ourselves away from here to meet Bill at Federation Concert Hall on Davey Street at 4.00 as pre-arranged. He told us that he’d had a quiet day which was probably just as well after all the driving he’s been doing on our behalf.

As mentioned earlier, Bill had taken us up Mount Nelson the day before because he wasn’t certain that the weather at the top of Mount Wellington would be sufficiently clear. On this occasion, he greeted us with the information that the weather was ideal and he very kindly drove us to the very top – a long way!

As mentioned earlier, Bill had taken us up Mount Nelson the day before because he wasn’t certain that the weather at the top of Mount Wellington would be sufficiently clear. On this occasion, he greeted us with the information that the weather was ideal and he very kindly drove us to the very top – a long way!

Mount Wellington, officially kunanyi / Mount Wellington, incorporating its Palawa kani name (Aboriginal: Unghbanyahletta or Poorawetter) is a mountain in the southeast coastal region of Hobart.

It is the summit of the Wellington Range and is within the Wellington Park reserve. Much of Hobart is located at the foothills of the mountain.

It is the summit of the Wellington Range and is within the Wellington Park reserve. Much of Hobart is located at the foothills of the mountain.

The mountain rises to 1,271 metres (4,170 ft) above sea level and is frequently covered by snow, sometimes even in summer. The lower slopes are thickly forested, but crisscrossed by many walking tracks and a few fire trails. There is also a sealed narrow road to the summit, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) from Hobart central business district.

An enclosed lookout near the summit has views of the city below and to the east, the Derwent estuary, and also glimpses of the World Heritage Area nearly 100 kilometres (62 mi) west. From Hobart, the most distinctive feature of Mount Wellington is the cliff of dolerite columns known as the Organ Pipes.

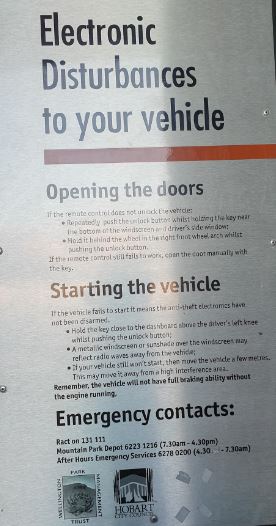

Perhaps the most alarming sign at the top for me was a notice that said that key fobs would possibly not open cars due to high electricity interference and that keys would have to be used. I was glad that I hadn’t brought my Tesla to the top of Mount Wellington!

Perhaps the most alarming sign at the top for me was a notice that said that key fobs would possibly not open cars due to high electricity interference and that keys would have to be used. I was glad that I hadn’t brought my Tesla to the top of Mount Wellington!

Back to the hotel for dinner and a quiet evening catching up.

Sunday was our last day and Bill had kindly offered to drive us to Port Arthur, a small town and former convict settlement on the Tasman Peninsula. It’s one of Australia’s most significant heritage areas and is effectively an enormous open-air museum.

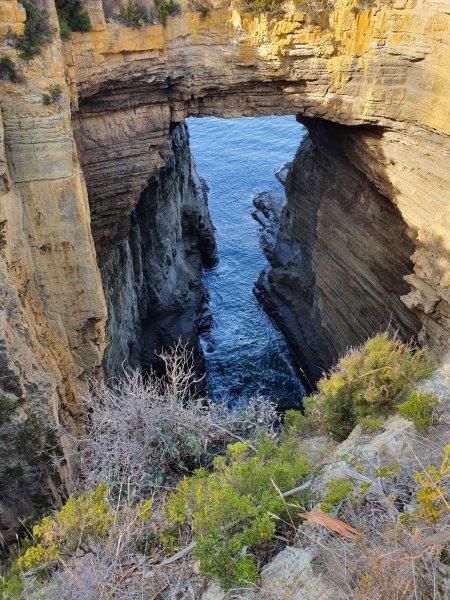

To reach Port Arthur, we passed through the narrow isthmus at Eaglehawk Neck. The east coast of this peninsula has several easy-to-reach wonders, including Tasmans Arch, Devils Kitchen, and the Tessellated Pavement. Bill drove us to all these delights and they were truly exceptional.

The first of these was Tasmans Arch where a cave’s roof has collapsed to form a bridged chasm. Tasman’s Arch is what’s left of the roof of a large sea cave, or tunnel that was created by wave action over many thousands of years. The pressure of water and compressed air, sand and stones acted on vertical cracks (joints) in the cliff, dislodging slabs and bounders. When you look into Tasmans Arch it seems to be old. While it may be old, it is still changing. Is the arch growing or is the roof thinning, or are the walls expanding? Below this viewing point and visible from the arch (opposite) is the entrance to a new cave, initiated by wave action. In the cliff-face opposite it was possible to see many weak zones, similar to those that gave way to create an arch when the cave roof collapsed. This immensely slow process of erosion is continuing. This arch will eventually collapse and another ‘Devils Kitchen’ will be formed.

The first of these was Tasmans Arch where a cave’s roof has collapsed to form a bridged chasm. Tasman’s Arch is what’s left of the roof of a large sea cave, or tunnel that was created by wave action over many thousands of years. The pressure of water and compressed air, sand and stones acted on vertical cracks (joints) in the cliff, dislodging slabs and bounders. When you look into Tasmans Arch it seems to be old. While it may be old, it is still changing. Is the arch growing or is the roof thinning, or are the walls expanding? Below this viewing point and visible from the arch (opposite) is the entrance to a new cave, initiated by wave action. In the cliff-face opposite it was possible to see many weak zones, similar to those that gave way to create an arch when the cave roof collapsed. This immensely slow process of erosion is continuing. This arch will eventually collapse and another ‘Devils Kitchen’ will be formed.

The next highlight in the area is Devils Kitchen which probably started as a sea cave, then a tunnel, and developed into its modern form after the collapse of the cave roof. It is one of several such coastal and forms in the Tasman National Park that have developed in the Permian-age siltstone.

The next highlight in the area is Devils Kitchen which probably started as a sea cave, then a tunnel, and developed into its modern form after the collapse of the cave roof. It is one of several such coastal and forms in the Tasman National Park that have developed in the Permian-age siltstone.

The siltstone cliffs in this area eroded unevenly to create these unique formations. This process started about 6,000 years ago as sea levels rose following the last ice age. Waves cut notches into the cliffs, suspending slabs of rock that eventually fell to create caves and shore platforms. Waves would erode away a joint in the rocks until it became a sea cave. The sea cave would grow deeper and become a tunnel, and continue to grow deeper and wider until the roof collapsed.

We watched waves wash over wave-cut platforms at sea level and smash into rock cliffs, knowing that these waves were ever-so-slowly eroding away the rock face. These waves exploit vertical joints in the rock to create caves that could eventually grow into natural bridges under the right circumstances.

Devils Kitchen and Tasmans Arch, as well as another nearby natural bridge called the Blowhole, all began as small caves chipped away by waves. Maybe in a few thousand years, there will be a new arch on this coastline.

Our final extraordinary sight was the Tessellated Pavement that is found at Lufra on Eaglehawk Neck. This tessellated pavement consists of a marine platform on the shore of Pirates Bay. This example consists of two types of formations: a pan formation and a loaf formation.

Our final extraordinary sight was the Tessellated Pavement that is found at Lufra on Eaglehawk Neck. This tessellated pavement consists of a marine platform on the shore of Pirates Bay. This example consists of two types of formations: a pan formation and a loaf formation.

The pan formation is a series of concave depressions in the rock that typically forms beyond the edge of the seashore. This part of the pavement dries out more at low tide than the portion abutting the seashore, allowing salt crystals to develop further; the surface of the "pans" therefore erodes more quickly than the joints, resulting in increasing concavity. The loaf formations occur on the parts of the pavement closer to the seashore, which are immersed in water for longer periods of time. These parts of the pavement do not dry out so much, reducing the level of salt crystallisation. Water, carrying abrasive sand, is typically channelled through the joints, causing them to erode faster than the rest of the pavement, leaving loaf-like structures protruding.

The loaf formations occur on the parts of the pavement closer to the seashore, which are immersed in water for longer periods of time. These parts of the pavement do not dry out so much, reducing the level of salt crystallisation. Water, carrying abrasive sand, is typically channelled through the joints, causing them to erode faster than the rest of the pavement, leaving loaf-like structures protruding.

The two narrow land bridges at Eaglehawk Neck and East Bay Neck at Dunalley made escape from the Port Arthur Convict Site which we were about to visit virtually impossible for the more than 12,000 men and young boys who were incarcerated within its dark and forbidding confines between 1831 and 1877.

By the middle of 1832 the officer’s quarters and soldier’s barracks at Eaglehawk Neck had been built to house one officer, a sergeant and twenty soldiers. Soon a store, guardhouse, several sentry boxes, a semaphore station, the infamous ‘dog line’ and a jetty stretching some 300 metres into Eaglehawk Bay were added. The garrison was later extended to house thirty to forty men.

With the closure of the Port Arthur penal settlement in 1877 the garrison at Eaglehawk Neck was abandoned. The land and buildings were then acquired by private settlers. In 1991 the site was acquired by the State Government and is now managed by the Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS).

With the closure of the Port Arthur penal settlement in 1877 the garrison at Eaglehawk Neck was abandoned. The land and buildings were then acquired by private settlers. In 1991 the site was acquired by the State Government and is now managed by the Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS).

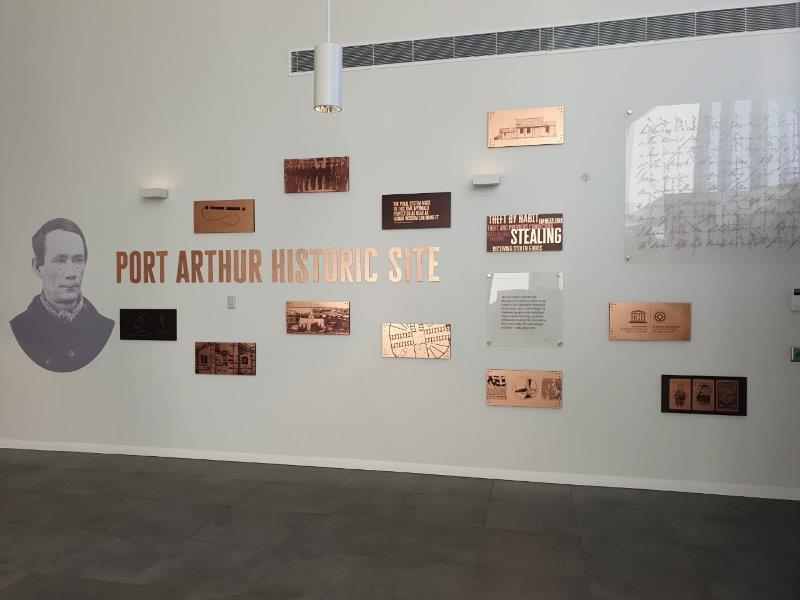

The Port Arthur Historic site forms part of the Australian Convict Sites, a World Heritage property consisting of 11 remnant penal sites originally built within the British Empire during the 18th and 19th centuries on fertile Australian coastal strips. Collectively, these sites, including Port Arthur, now represent, ‘...the best surviving examples of large-scale convict transportation and the colonial expansion of European powers through the presence and labour of convicts.’

Port Arthur is located approximately 97 kms south east Hobart and has a population of about 250. The scenic drive from Hobart, via the Tasman Highway took us about 90 minutes. Transport from Hobart to the site is also available via bus or ferry, and various companies offer day tours from Hobart.

Port Arthur is located approximately 97 kms south east Hobart and has a population of about 250. The scenic drive from Hobart, via the Tasman Highway took us about 90 minutes. Transport from Hobart to the site is also available via bus or ferry, and various companies offer day tours from Hobart.

Port Arthur was named after George Arthur, the lieutenant governor of Van Diemen’s Land. The settlement started as a timber station in 1830, but it is best known for being a penal colony.

From 1833 until 1853, it was the destination for the hardest of convicted British criminals, those who were secondary offenders having re-offended after their arrival in Australia. Rebellious personalities from other convict stations were also sent there. In addition, Port Arthur had some of the strictest security measures of the British penal system.

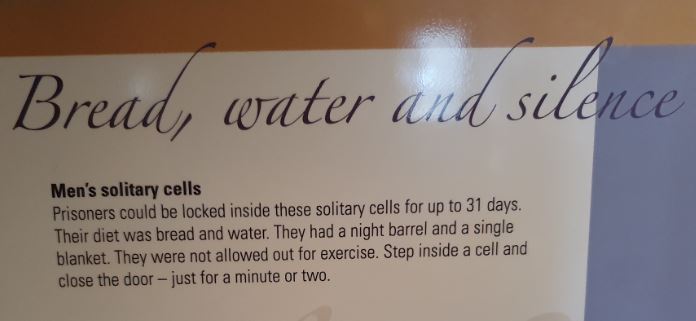

The prison was completed in 1853, but then extended in 1855. The Separate Prison System also signaled a shift from physical punishment to psychological punishment. The hard corporal punishment, such as whippings, used in other penal stations was thought to only serve for hardened criminals and did nothing to turn them from their immoral ways. For example, food was used to reward well-behaved prisoners and as punishment for troublemakers. As a reward, a prisoner could receive larger amounts of food or even luxury items such as tea, sugar, and tobacco. As punishment, the prisoners would receive the bare minimum of bread and water.

The prison was completed in 1853, but then extended in 1855. The Separate Prison System also signaled a shift from physical punishment to psychological punishment. The hard corporal punishment, such as whippings, used in other penal stations was thought to only serve for hardened criminals and did nothing to turn them from their immoral ways. For example, food was used to reward well-behaved prisoners and as punishment for troublemakers. As a reward, a prisoner could receive larger amounts of food or even luxury items such as tea, sugar, and tobacco. As punishment, the prisoners would receive the bare minimum of bread and water.

Under this system of punishment, the ‘Silent System’ was implemented in the building. Here, prisoners were hooded and made to stay silent; this was supposed to allow time for the prisoner to reflect upon the actions that had brought him there. Many of the prisoners in the Separate Prison developed mental illness from the lack of light and sound. This was an unintended outcome, although an asylum was built right next to the Separate Prison.

The peninsula on which Port Arthur is located is a naturally secure site by being surrounded by water (rumoured by the administration to be shark-infested). The isthmus of Eaglehawk Neck was the only connection to the mainland and this was fenced and guarded by soldiers, man traps, and half-starved dogs.

The peninsula on which Port Arthur is located is a naturally secure site by being surrounded by water (rumoured by the administration to be shark-infested). The isthmus of Eaglehawk Neck was the only connection to the mainland and this was fenced and guarded by soldiers, man traps, and half-starved dogs.

Contact between visiting seamen and prisoners was barred. Ships had to check in their sails and oars upon landing to prevent any escapes. However, many attempts were made, and some were successful. Boats were seized and rowed or sailed long distances to freedom. Shore-based and ship-based whaling was banned in the area to prevent convicts trying to escape in the boats.

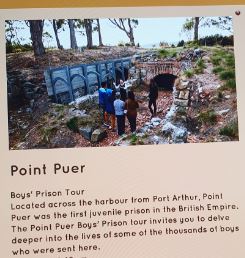

Port Arthur was reputed to be an inescapable prison, much like the later Alcatraz Island in the United States but some prisoners were not discouraged by this, and tried to escape. It was also the destination for juvenile convicts, receiving many boys, some as young as nine. The boys were separated from the main convict population and kept on Point Puer, the British Empire’s second boys' prison. Like the adults, the boys were used in hard labour such as stone cutting and construction. One of the buildings constructed was one of Australia's first nondenominational churches, built in gothic style. Attendance of the weekly Sunday service was compulsory for the prison population. Critics of the new system noted that this and other measures seemed to have negligible impact on reformation.

Port Arthur was reputed to be an inescapable prison, much like the later Alcatraz Island in the United States but some prisoners were not discouraged by this, and tried to escape. It was also the destination for juvenile convicts, receiving many boys, some as young as nine. The boys were separated from the main convict population and kept on Point Puer, the British Empire’s second boys' prison. Like the adults, the boys were used in hard labour such as stone cutting and construction. One of the buildings constructed was one of Australia's first nondenominational churches, built in gothic style. Attendance of the weekly Sunday service was compulsory for the prison population. Critics of the new system noted that this and other measures seemed to have negligible impact on reformation.

Despite its reputation as a pioneering institution for the new, enlightened view of imprisonment, Port Arthur was still in reality as harsh and brutal as other penal settlements. Some critics might even suggest that its use of psychological punishment, compounded with no hope of escape, made it one of the worst. Some tales suggest that prisoners committed murder (an offence punishable by death) just to escape the desolation of life at the camp.

The Isle of the Dead was the destination for all who died inside the prison camps. The mass graves on the Isle attract visitors. The air about the small, bush-covered island is described as possessing ‘melancholic’ and ‘tranquil’ qualities by visitors. Of the 1,646 graves recorded to exist there, only 180, those of prison staff and military personnel, are marked. Julie and I took a boat trip which included a circumnavigation of this minute island which is every bit as small as it looks. It was hard to imagine so many bodies being buried there.

The Isle of the Dead was the destination for all who died inside the prison camps. The mass graves on the Isle attract visitors. The air about the small, bush-covered island is described as possessing ‘melancholic’ and ‘tranquil’ qualities by visitors. Of the 1,646 graves recorded to exist there, only 180, those of prison staff and military personnel, are marked. Julie and I took a boat trip which included a circumnavigation of this minute island which is every bit as small as it looks. It was hard to imagine so many bodies being buried there.

Before Port Arthur was abandoned as a prison in 1877, some people saw its potential as a tourist attraction. David Burn, who visited the prison in 1842, was awed by the peninsula's beauty and believed that many would come to visit it. This opinion was not shared by all. For example, Anthony Trollope in 1872 declared that no man desired to see the ‘strange ruins’ of Port Arthur. In place of the Prison Port Arthur, the town of Carnarvon was born, named after the British Secretary of State, and the population was said to be ‘refined and intellectual.’

Before Port Arthur was abandoned as a prison in 1877, some people saw its potential as a tourist attraction. David Burn, who visited the prison in 1842, was awed by the peninsula's beauty and believed that many would come to visit it. This opinion was not shared by all. For example, Anthony Trollope in 1872 declared that no man desired to see the ‘strange ruins’ of Port Arthur. In place of the Prison Port Arthur, the town of Carnarvon was born, named after the British Secretary of State, and the population was said to be ‘refined and intellectual.’

In 1927, tourism had grown to the point where the area's name was reverted to Port Arthur. In 1916, the Scenery Preservation Board (SPB) was established to take the management of Port Arthur out of the hands of the locals. By the 1970s, the National Parks and Wildlife Service began managing the site. In 1979, funding was received to preserve the site as a tourist destination, due to its historical significance. Several magnificent sandstone structures, built by convicts working under hard labour conditions, were cleaned of ivy overgrowth and restored to a condition similar to their appearance in the 19th century. Buildings include the "Model Prison", the Guard Tower, the Church, and the remnants of the main penitentiary. The buildings are surrounded by lush, green parkland.

Point Puer, across the harbour from the main settlement, was the site of the first boys' reformatory in the British Empire. Boys sent there were given some basic education, and taught trade skills.

Point Puer, across the harbour from the main settlement, was the site of the first boys' reformatory in the British Empire. Boys sent there were given some basic education, and taught trade skills.

The museum contains written records, tools, clothing, and other curiosities from convict times, a convict gallery with displays of the various trades and work undertaken by convicts, and a research room where visitors can check up on any convict ancestors.

The World Heritage Committee of UNESCO inscribed the Port Arthur Historic Site and the Coal Mines Historic Site onto the World Heritage Register on 31 July 2010, as part of the Australian Convict Sites World Heritage property. To this day, Port Arthur is one of Australia's best-known historical sites, receiving over 250,000 visitors each year and the government puts significant money into the site’s upkeep. It is inevitable that the site will be affected by rising sea waters level in the coming years due to global warming, a problem that has been noticed all over Southern Australia.

Quite separately from the convict history, Port Arthur was the scene of the worst mass murder event in post-colonial Australian history in 1966. On 28 April 1996, the Port Arthur historic site was the location of a killing spree. The perpetrator murdered 35 people and wounded 23 more before being captured by the Special Operations Group. This led to a national restriction on high capacity semiautomatic shotguns and rifles. The perpetrator, 28-year-old Martin Bryant, was subsequently convicted, and is currently serving 35 life sentences plus 1,035 years without parole in the psychiatric wing of Risdon Prison in Hobart. Reading up on Port Arthur’s history before our visit we were asked not to mention this massacre to any of the people who work there as many of them lost friends and relatives during the massacre.

Quite separately from the convict history, Port Arthur was the scene of the worst mass murder event in post-colonial Australian history in 1966. On 28 April 1996, the Port Arthur historic site was the location of a killing spree. The perpetrator murdered 35 people and wounded 23 more before being captured by the Special Operations Group. This led to a national restriction on high capacity semiautomatic shotguns and rifles. The perpetrator, 28-year-old Martin Bryant, was subsequently convicted, and is currently serving 35 life sentences plus 1,035 years without parole in the psychiatric wing of Risdon Prison in Hobart. Reading up on Port Arthur’s history before our visit we were asked not to mention this massacre to any of the people who work there as many of them lost friends and relatives during the massacre.

And so we came to the end of a wonderful week exploring the Australian State of Tasmania. We will have great memories and have much to thank our guide and driver, Bill (seen here chatting up one of the one-time dignatories of Strahan on the third day of our trip) for the wonderful whirlwind tour he took us on of the country he now calls ‘home’ (although a New Zealander by birth).

He returned us safely to our hotel beside the airport ready for our flight to Sydney and Kate and family the following day.

But that’s another story …