The day dawned bright and sunny and it was fairly warm although there was a tiny breeze we could feel when we were in the shade. The area is covered in trees so we were rarely exposed to full sunshine.

Today Lewis, Gina and I had an exclusive excursion for just the three of us. Many of the passengers were disembarking from the Road to Mandalay and many more would be arriving at

Today Lewis, Gina and I had an exclusive excursion for just the three of us. Many of the passengers were disembarking from the Road to Mandalay and many more would be arriving at

Pyae and our driver took us on a tour of Sagaing. As

Pyae and our driver took us on a tour of Sagaing. As

The Yadanabon Bridge spans the Ayeyarwady River in the Mandalay suburb that connected with Sagaing City. It is 610 m upstream of the Ava Bridge which is at the confluence of the Ayeyarwady with the Myitnge River, close to the Jyayujse rice fields. The bridge is the gateway to Yangon, Mandalay and other regions in the interior.

The Yadanabon Bridge spans the Ayeyarwady River in the Mandalay suburb that connected with Sagaing City. It is 610 m upstream of the Ava Bridge which is at the confluence of the Ayeyarwady with the Myitnge River, close to the Jyayujse rice fields. The bridge is the gateway to Yangon, Mandalay and other regions in the interior.

The old Ava bridge across the Ayeyarwady River had a span of 1,203 m. Built by the British in 1934, it was the only bridge that spanned this river until the 1990s. The Ava had aged, and its carrying capacity became limited to under 15-ton trucks since 1992. Heavily laden vehicles crossed the river with Z-craft ferries, resulting in less efficient transportation of goods.

The new Ayeyarwady Bridge was built by the Public Works of the Ministry of Construction. It now has

We crossed the new Yatanabon Bridge into Sagaing! It has a wonderfully peaceful feeling.

In the Sagaing hills, 20km to the southwest of the ancient capital of Mandalay and on the opposite bank of the river in Upper Myanmar there are hundreds of pagodas, stupas, numerous monasteries, nunneries and learning

The monks and nuns make ends meet in a very distinctive way - they are entirely dependent on lay people for their daily existence, living from hand to mouth on donations. Unlike Christian nuns and monks, Buddhist monastic communities are not supposed to involve themselves in any form of livelihood activity but must be kept by donors, who by giving donations, build up spiritual merit for their next life - and worldly success in this one.

Nunneries and monasteries don't just consist of adults. Although all members are celibate, they live in groups like families, including small children as young as five. Some of these little children stay a week as temporary monks or nuns; others stay their whole lives. The days of the monks and nuns are taken up with prayer, study, household work, chanting

Monasteries are not divided

The networks of donors on which the nuns and monks of Sagaing depend show how important a strong set of social relations is to people's livelihoods - what is sometimes called social capital. The interdependence between nuns and monks on the one hand and lay people on the other seems to be one which benefits both

The monastic communities may also be said to have something we might call `spiritual capital'. The monks and nuns are happy people. The fact that they are interlinked and dependent on their donors is something which gives them a sense of strength and of being needed, and this is almost certainly important in giving them a sense of peace and stability. But their spirituality is also important in establishing their own serenity. It also ensures that donors will keep giving to them.

Donors benefit from the relationship with the monastic community in terms of their own state of mind. They get a sense of security and stability from

Sagaing was the capital of Sagaing Kingdom (1315–1364), one of the minor kingdoms that rose up after the fall of Pagan dynasty. During the Ava period (1364–1555), the city was the common fief of the crown prince or senior princes. The city briefly became the royal capital between 1760 and 1763 in the reign of King Naungdawgyi.

On August 8, 1988, Sagaing was the site of demonstrations which were concluded by a massacre in which around 300 civilians were killed.

Today, with about 70,000 inhabitants, the city is part of Mandalay’s built-up area with more than 1,022,000 inhabitants estimated in 2011. The city is a frequent tourist destination for

The central pagoda is Soon U Ponya Shin Pagoda.

The central pagoda is Soon U Ponya Shin Pagoda.

It is connected by a set of covered staircases that run up the 240m hill. The covering is a very clever idea because the climb is significant and it means that people can walk up without fear of getting drenched in the rainy season.

It is connected by a set of covered staircases that run up the 240m hill. The covering is a very clever idea because the climb is significant and it means that people can walk up without fear of getting drenched in the rainy season.

Inside there is the obligatory statue of a Buddha, on this occasion, surrounded by beautiful stonework on all sides.

Inside there is the obligatory statue of a Buddha, on this occasion, surrounded by beautiful stonework on all sides.

The ceiling was very ornate too where it almost seemed a shame that things like light bulbs and sprinklers detracted from the original design.

The ceiling was very ornate too where it almost seemed a shame that things like light bulbs and sprinklers detracted from the original design.

Very young novice monks were all over the place, usually pretty close to the donation boxes which were everywhere. Children can join a monastery or a nunnery any time between the ages of 6 and 20 for as short a period as a day or forever. It is expected that everyone will join one or other at least twice during their life, but the length of time doesn’t appear to be relevant.

Very young novice monks were all over the place, usually pretty close to the donation boxes which were everywhere. Children can join a monastery or a nunnery any time between the ages of 6 and 20 for as short a period as a day or forever. It is expected that everyone will join one or other at least twice during their life, but the length of time doesn’t appear to be relevant.

Outside all the floors were marble with many different patterns and

Outside all the floors were marble with many different patterns and

And Gina, Lewis and I enjoyed everything that Pyae had to tell us about the history of the

And Gina, Lewis and I enjoyed everything that Pyae had to tell us about the history of the

From here we could enjoy the expansive 360-degree views in all directions from the high vantage point.

From here we could enjoy the expansive 360-degree views in all directions from the high vantage point.

From Soon U Ponya Shin Pagoda we drove down the hill to the Zayar Theingi Nunnery.

From Soon U Ponya Shin Pagoda we drove down the hill to the Zayar Theingi Nunnery.

The entrance was rather unimposing but the nuns of varying

The entrance was rather unimposing but the nuns of varying  ages inside were delightful, from these two very young girls to these two older nuns, one of which (on the right) told us that she had entered the nunnery at the age of 10 and that she was now 40. They were cutting up and dispensing

ages inside were delightful, from these two very young girls to these two older nuns, one of which (on the right) told us that she had entered the nunnery at the age of 10 and that she was now 40. They were cutting up and dispensing

Sagaing is famous for the silverware its artisans produce and we visited a workshop where they

Sagaing is famous for the silverware its artisans produce and we visited a workshop where they

Pieces are cut off from an ingot made of silver like this one – which is remarkably heavy. Differently sized pieces can obviously be melted down to make

Pieces are cut off from an ingot made of silver like this one – which is remarkably heavy. Differently sized pieces can obviously be melted down to make

A substance (that includes wax) is poured into the inside of the bowl (in this case) and a piece of wood is fixed in the middle while it cools.

A substance (that includes wax) is poured into the inside of the bowl (in this case) and a piece of wood is fixed in the middle while it cools.

And then artisans like this one can create designs before the article is finished.

And then artisans like this one can create designs before the article is finished.

There was so much on offer and I couldn’t resist buying a minute tortoise – a symbol of peace in Myanmar – actually made of bronze and silver plated. As I bought him in Myanmar, I will be calling him by a Burmese name - Tun. He will be a friend

We’d been having a very busy day up to this point but we soon discovered that it was only just beginning. We went back to the boat for lunch and then set off again for Htin-Win – a short little boat ride across the river.

As we crossed over the ‘gangplank’ to the shore we came across some local women doing their washing in river water that looked none too clean. Having said that, the clothes that were laid out on the rocks above them looked as clean as they always do when they wear them so the

As we crossed over the ‘gangplank’ to the shore we came across some local women doing their washing in river water that looked none too clean. Having said that, the clothes that were laid out on the rocks above them looked as clean as they always do when they wear them so the

As we drove along the road we passed a couple of sights that reminded us of how much work has to be done everywhere to raise the standard of living in the city and made some of our poorer areas in New Zealand look luxurious in comparison. These apartments, for example, had no land around to cultivate or develop.

As we drove along the road we passed a couple of sights that reminded us of how much work has to be done everywhere to raise the standard of living in the city and made some of our poorer areas in New Zealand look luxurious in comparison. These apartments, for example, had no land around to cultivate or develop.

Building work is obviously going on, albeit slowly, but the scaffolding would never pass the OSH standards in New Zealand!

Building work is obviously going on, albeit slowly, but the scaffolding would never pass the OSH standards in New Zealand!

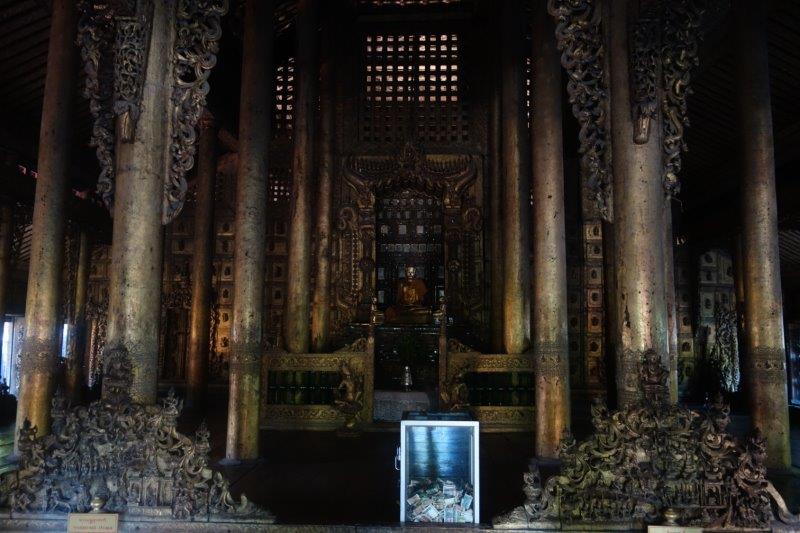

We were bound for Shwenandaw Monastery, known as Golden Palace Monastery, located near Mandalay Hill.

We were bound for Shwenandaw Monastery, known as Golden Palace Monastery, located near Mandalay Hill.

Shwenandaw Monastery was built in 1880 by King Thibaw Min who dismantled and relocated the apartment formerly occupied by his father, King Mindon Min just before Mindon Min's death, at a cost of 120,000 rupees. Thibaw removed the building in October 1878, believing it to be haunted by his father's spirit. The building was reconstructed as a monastery over the course of 5 years, dedicated in memory of his father, on a plot adjoining Atumashi Monastery.

The building was originally part of the royal palace at

The monastery is known for its teak carvings of Buddhist myths, which adorn its walls and roofs. It is built in the traditional Burmese architectural style. Shwenandaw Monastery is the single remaining major original structure of the original Royal Palace today.

The monastery is known for its teak carvings of Buddhist myths, which adorn its walls and roofs. It is built in the traditional Burmese architectural style. Shwenandaw Monastery is the single remaining major original structure of the original Royal Palace today.

We’d all noticed over our stay here that nearly every sign is in the language of the country, whether that’s Burmese, Pali or a local dialect. There were

We’d all noticed over our stay here that nearly every sign is in the language of the country, whether that’s Burmese, Pali or a local dialect. There were  hardly any signs translated into English which gave an indication of how little tourism has encroached into this beautiful country. We were all fascinated, therefore, to see that a couple of the signs in the monastery were very clearly in English!

hardly any signs translated into English which gave an indication of how little tourism has encroached into this beautiful country. We were all fascinated, therefore, to see that a couple of the signs in the monastery were very clearly in English!

Soe had told us during his talk on Buddhism a few days earlier that this sign was quite common in the inner sanctum of Monasteries – and he thought it was inappropriate (what else could he possibly say to a mixed audience?) as there was nothing in Buddha’s teachings that gave rise to this directive.

From here we went to Kuthodaw Pagoda which is a Buddhist stupa that contains the world’s largest book. It lies at the foot of Mandalay Hill and was built during the reign of King Mindon.

From here we went to Kuthodaw Pagoda which is a Buddhist stupa that contains the world’s largest book. It lies at the foot of Mandalay Hill and was built during the reign of King Mindon.

The stupa itself, which is gilded above its terraces, is 57m high and is

The stupa itself, which is gilded above its terraces, is 57m high and is

Mindon Min had the Pagoda built as part of the traditional foundations of the new royal city of Mandalay in 1857. He was later to convene the Fifth Buddhist Synod in

In the grounds of the Pagoda are 729

In the grounds of the Pagoda are 729

Between the rows of stone-inscription stupas grow mature star flower trees (Mimusops

Between the rows of stone-inscription stupas grow mature star flower trees (Mimusops

The history of the

This however turned to great sadness when they found that the pagoda had been looted with the

Leaving the Kuthodaw Pagoda, we made our way to a gold leaf beating factory. Preferring gold to silver, I expected to find myself tempted to buy but in

Leaving the Kuthodaw Pagoda, we made our way to a gold leaf beating factory. Preferring gold to silver, I expected to find myself tempted to buy but in

These men beat the gold between two pieces of very fine wood for two hours at a stretch. They have a

There are more processes of course but this room contained women and children delicately lifting the gold leaf with a small implement and putting each leaf into a plastic sleeve. Some were sitting on a cushion but most were sitting on the hard marble floor and they appeared to remain there for hours on end.

There are more processes of course but this room contained women and children delicately lifting the gold leaf with a small implement and putting each leaf into a plastic sleeve. Some were sitting on a cushion but most were sitting on the hard marble floor and they appeared to remain there for hours on end.

The final product was displayed together with the steps taken to reach it. Of course, gold leaf is in high demand because the Buddhist people buy it to place on the various statues all over the country. Suh is the immensely strong belief of the people that they will buy large quantities of gold leaf to place on the religious statues of the Buddhas.

The final product was displayed together with the steps taken to reach it. Of course, gold leaf is in high demand because the Buddhist people buy it to place on the various statues all over the country. Suh is the immensely strong belief of the people that they will buy large quantities of gold leaf to place on the religious statues of the Buddhas.

And so we set off again, this time bound for U Bein Bridge, a crossing that spans the Taungthaman Lake near Amarapura. The 1.2 km bridge is believed to be the oldest and longest teakwood bridge in the world. We were to see it in the sunset. This experience will remain in my memory for a long time. It was very special and probably my

And so we set off again, this time bound for U Bein Bridge, a crossing that spans the Taungthaman Lake near Amarapura. The 1.2 km bridge is believed to be the oldest and longest teakwood bridge in the world. We were to see it in the sunset. This experience will remain in my memory for a long time. It was very special and probably my

Construction of the bridge began when the capital of Ava Kingdom moved to Amarapura and the bridge is named after the mayor who had it built. It is used as an important passageway for the local people and has also become a tourist attraction and therefore a significant source of income for souvenir sellers. It is particularly busy during July and August when the lake water is at its highest level.

The bridge was built from wood reclaimed from the former royal palace in Inwa. It features 1,086 pillars that stretch out of the water, some of which have been replaced with concrete. Though the bridge largely remains intact, there are fears that an increasing number of the pillars are becoming dangerously decayed. Some have become entirely detached from their bases and only remain in place because of the lateral bars holding them together. Damage to these supports has been caused by flooding as well as a fish breeding program introduced into the lake which has caused the water to become stagnant. The Ministry of Culture’s Department of Archaeology, National Museum and Library, plans to carry out repairs when plans for the work are

Eight police force personnel have been deployed to guard the bridge. Their presence is aimed at reducing anti-social

The construction was started in 1849 and finished in 1851. Myanmar construction engineers used traditional methods of scaling and measuring to build the bridge. According to historical books about U Bein Bridge, Myanmar engineers made scale by counting the footsteps. The bridge was built in a curved shape in the middle to resist the assault of wind and water. The main teak posts were hammered into the lake bed seven feet deep. The other ends of the posts were shaped conically to make sure that rainwater fell past them easily. The joints were intertwined.

Originally, there were 984 teak posts supporting the bridge and two approach brick bridges. Later the two approach brick bridges were replaced by wooden approach bridges. There are four wooden pavilions at the same intervals along the bridge. By adding posts of two approach bridges and four pavilions, the number of posts amounts to 1089.

There are nine passageways in the bridge, where the floors can be lifted to let large boats and barges pass. There are 482 spans altogether and the total length of the bridge measures 3967 feet or three-quarters of a mile.

Our SUV arrived at the landing area and people converged from all sides to board one of the very many small boats, manned by oarsmen, to set off into the lake before the sunset. Our oarsman was excellent and soon took us out into the middle of the lake.

Our SUV arrived at the landing area and people converged from all sides to board one of the very many small boats, manned by oarsmen, to set off into the lake before the sunset. Our oarsman was excellent and soon took us out into the middle of the lake.

Imagine our surprise when another boat came towards us and we

Imagine our surprise when another boat came towards us and we

Glasses poured for us, they moved on to other passengers from the Road to Mandalay and we sipped our champagne as we watched the sun sink below the bridge with the hundreds of spectators walking along its length. Of course, I took countless photos to catch the setting sun, thinking that each one would be my last chance, only to find that the sun sank really slowly and the next one was even better. This is just one of them.

Glasses poured for us, they moved on to other passengers from the Road to Mandalay and we sipped our champagne as we watched the sun sink below the bridge with the hundreds of spectators walking along its length. Of course, I took countless photos to catch the setting sun, thinking that each one would be my last chance, only to find that the sun sank really slowly and the next one was even better. This is just one of them.

If we thought this was the end of our day, we had another think coming (as the ungrammatical saying goes)!

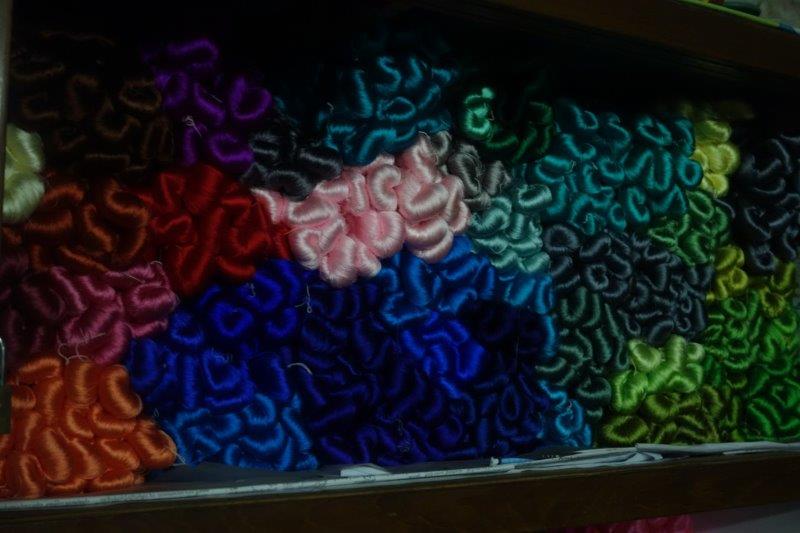

We were off to a silk weaving factory.

We were off to a silk weaving factory.

Silk is not made in Myanmar because the strong Buddhist influence will not allow the silkworms to be harmed so the raw material comes in from China or Thailand. And it comes in like this, in the most beautiful

Silk is not made in Myanmar because the strong Buddhist influence will not allow the silkworms to be harmed so the raw material comes in from China or Thailand. And it comes in like this, in the most beautiful

From here it is put onto spools, then

From here it is put onto spools, then  small bobbins and finally the expert weavers begin the weaving process, sometimes using as many as 35 bobbins apiece.

small bobbins and finally the expert weavers begin the weaving process, sometimes using as many as 35 bobbins apiece.

The finished products are displayed in the shop of course.

The finished products are displayed in the shop of course.

If Gina and I hadn’t been so tired by this time we might have taken the time to buy up big. As it was, it was all just too hard for us to make choices and we came away empty handed.

I don’t think the day could have been any fuller. Belmond is certainly making sure that we have a truly memorable experience.